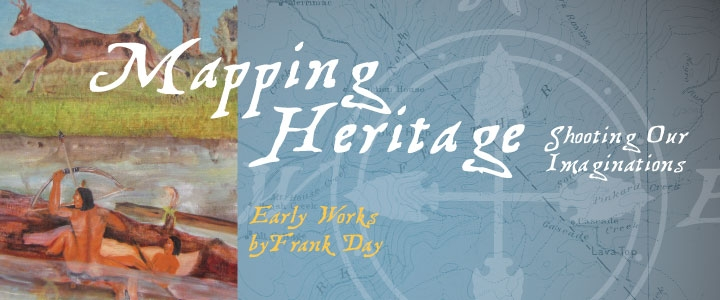

Mapping Heritage, Shooting Our Imaginations

Mapping Heritage, Shooting Our Imaginations

Early Works by Frank Day

Exibition Dates: September 30, 2013 - October 24, 2013

Artist Statement

“One of the reasons I'm doing this, to make these things clear, [is] that one day it may be used for a good purpose. It's going to shoot all of your imaginations of what a California Indian is, because you don't know it. You don't know much about 'em, unless you are one." —Frank Day, 1975

Frank Day, LY-DAM-LILLY (Fading Morning Star), was a self-taught Konkow Maidu artist. But he was also a bearer of his culture’s traditions and customs, of the language, history, and legends that formed the foundation of his Maidu heritage, all of which are deeply bound to the physical landscape. As an artist and Maidu traditionalist, he was moved to bring Maidu tradition into the present, to give tradition continuity in a changing world. It is the goal of this exhibit to highlight the many ways Frank Day mapped his world, his heritage, and his life through his paintings, while also charting his lasting and expansive influence in the arts and on contemporary California Indian and Native American expressive culture.

Day was born in 1902 in Berry Creek—northeast of Oroville, along Feather River country—where his father, Billy Day or Twoboe, was a respected headman and leader. As a headman, Twoboe assumed the role of the keeper of Maidu knowledge as well as the transmitter of it, for knowledge of Maidu tradition is only meaningful if it is practiced, if it is lived in every moment of the day. Day continued his father’s work by passing his knowledge on, keeping the knowledge alive through his vivid and figurative paintings, as well as through song and dance.

Day began to paint in 1960, as he recovered from a disabling work-related injury. This marked a turning point in Day’s life, artistic career and cultural influence. By 1967, he had painted more than 250 stories, effectively creating a map of Maidu life, language and landscape. By the time of his passing in 1976, Day’s art was renowned in and out of Native art communities and exhibited across the country. Although his more well known and “mature” works were painted during the mid-1970s, when he enjoyed the financial support and exposure made possible by the patronage of Pacific Western Traders, the works exhibited here date to the previous decade and represent Day’s early efforts to bring Maidu life into the center of modern society and to challenge the status quo by re-presenting California Indian culture and tradition from the inside.

Through his paintings, Day proposed to ‘shoot our imaginations,’ to show non-Natives a different view of Native Americans, one that was self-determined and self-represented. Eager to bring to light the significance of Maidu lifeways and to keep the Spirit of Maidu culture alive for his people, but also dissatisfied with the limitations of language and worldview faced by non-Maidu anthropologists and historians who tried to record and preserve Maidu traditions, Day took the helm and painted what he knew. Through his imagination we expand our own, we shoot through our preconceptions of what it means to be a Native American, of what tradition means in the present to Native peoples. By mapping Day’s imagination through his paintings, his landscapes of tradition, we are able not only to visualize the traditions and customs they illustrate, but to place them as well—to imprint them on the Earth and imbue them with life.

Tradition is an active endeavor; it requires the concerted effort of all who participate in it. As visitors to this exhibit, we hope that you, whether of Native or non-Native heritage, will be able to experience these paintings and thus take part in reaffirming the traditions they portray and the wider worlds in which they were borne. The maps and words that accompany each of the paintings serve to orient our imaginations—or re-orient them—so that we can engage in Day’s work, his imagination, and his influence from a more meaningful place.

—Valerie Garcia and Terri Castaneda, Department of Anthropology, Sacramento State

Quick Information

Name

The Gallery

Phone

916-278-7250

Email

Hours

Can’t find what you are looking for? Contact the University Union Info Desk at 916-278-6997 or email uuinfodesk@csus.edu

The University Union is located at California State University, Sacramento 6000 J Street, Sacramento, CA 95819